.png)

Each winter, starlings gather in huge flocks around the UK. Some are native, but many migrate from colder northern European countries. They are here because our winters are milder and they can find food and shelter before returning north to breed in the spring.

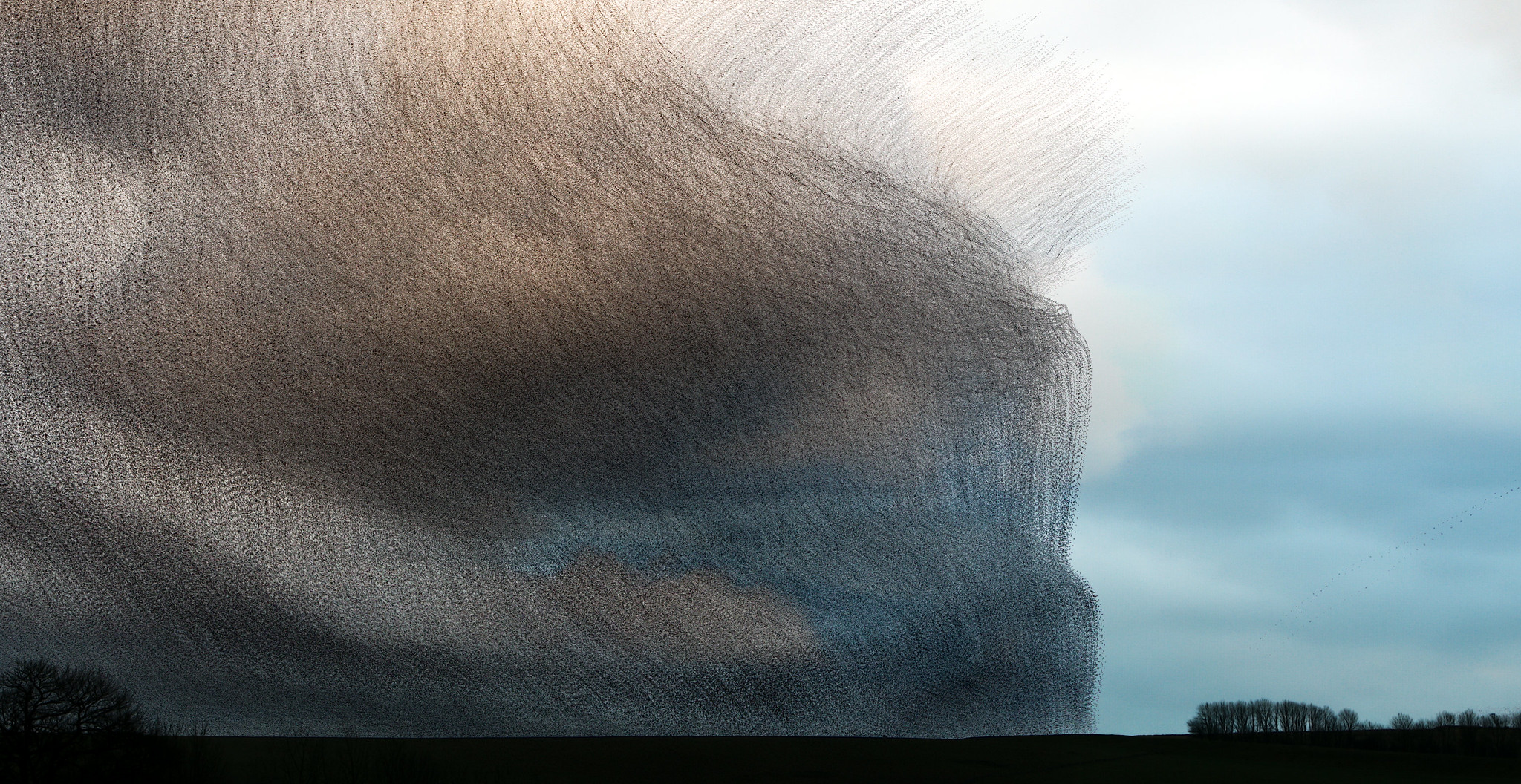

Some gatherings have been reported to number over a million birds. They have preferred sites where they return to year after year, but their presence is not always guaranteed.

This season I focused on a starling roost on Middleton Moor, above the Derbyshire village of Stoney Middleton. This was once a working village, home to many limestone quarries. With their closure, much of the site has been reclaimed by nature.

As dusk approaches, groups of starlings arrive in dribs and drabs, coming in to roost after feeding in the fields. Then, as if out of nowhere, thousands of birds appear on the horizon.

I have been studying their behaviour for the past three winters. During that time I have been refining a modern take on the Victorian photographic technique of chronophotography, where a sequence of images are captured to study motion. I am interested in the transient moments when chaos briefly changes to order - moments where thousands of individual bodies appear to move as one.

Sometimes the flock is so large that it fills the horizon like a curtain of smoke. As they pass overhead, the sky darkens and the sound of thousands of wingbeats fills the air.

Early in the season, predators were scarce. Large groups of starlings arrived above the reedbeds, and then, in a swift and orderly way they descended to the safety of the reeds. These large groups would descend in stages, a few heading down towards the reeds and the rest remaining at a safe height. As if this is part of some strategy to safeguard against predation, or perhaps there is only so much roosting space in each section of reeds.

As birds descend into the reedbed, others burst upward again, disturbed by the new arrivals. Once all settled, the chattering of hundreds of thousands of birds continues as I make my way back to my car in darkness.

As winter progresses, predators gather in the coppices surrounding the reeds. Every ten minutes or so a sparrowhawk would appear from the trees for a short-lived pursuit, flying beneath the flock to keep the starlings off the safety of the reedbed. This continued until near-darkness. It was difficult to tell how many predators were present. Certainly more than one; perhaps benefitting from the combined efforts to split and tire the flock.

My main aim this winter was to capture some predator-prey interaction. I could see glimpses of the flock being split by the predators but the fast pace and rapid changes of direction made planning my shots difficult.

Anticipating how the flock would react was crucial to framing the action. Each image is the result of hundreds of hours of observation and filming the birds. Only on processing my footage did I find that I had captured a few intense moments where the birds of prey caused the starlings to scatter.

Even when the hawks are elsewhere the predators have the starlings on edge and the flock twists and turns as if being pursued. The swirling mass of birds can seem to appear out of nowhere, and just as quickly vanish. The fleeting shapes and patterns are a result of a precise mix of weather, season, food and predation and will never again be repeated.

I visited throughout the winter, starting in November. At peak numbers in January, there were hundreds of thousands of birds forming a vast swirling carpet over the moors. During February they started to disperse. And then, suddenly, one evening in March, they were gone.

----------~----------

These images were put together as part of a project on the theme of “Nowhere”, the theme for the 2020 Cley Contemporary Art Exhibition. Hanging them at Cley will now go ahead in July 2021, as the exhibition has been postponed due to the Coronavirus pandemic.